Saturday, July 5, 2014

Baby Owls!

Posted by

Lillian Stokes

Here's a photo of baby Great Horned Owls I took in Florida. They had moved out onto the branch from their nest. During the sixth to eighth week after they hatch, young Great Horned Owls leave the nest and may perch on nearby branches before taking their first flights. It can sometimes happen that the young leave the nest earlier because of a flimsy nest or other disturbance and in that case they may perch on the ground at the base of the tree and the parents bring them food. After the young fledge and can fly, they stay perched in the territory and wait for food to be brought to them. At nine to ten weeks of age they begin sustained flights and may follow after the parents and call loudly. They gradually develop their flying ability and learn how to hunt. At five months they are ready to live on their own and parents and young disperse off the territory. So cute at this age, then they grow up to be one of the fiercest avian predators in the woods.

Thursday, July 3, 2014

Butcher Bird in early field guides

Posted by

Kenneth Cole Schneider

Shades of gray can be beautiful, but also confusing to a young birder.

Back in New Jersey on August 21, 1949 I saw my first Loggerhead Shrike. It was my Life Bird #119. Actually, a few days earlier I had found grasshoppers impaled on the spikes of a barbed wire fence in the Passaic River bottomlands a short walk from my home in Rutherford.

I had read about how the "Butcher Bird," whose "weak feet" lacked the talons of raptors, must stabilize its victims in this manner to permit them to be torn apart with its hooked beak. Hoping one day to see mice and small birds in a shrike's larder, I did not expect lowly insects. I searched for the shrike to no avail until three days later, when I caught sight of my "lifer."

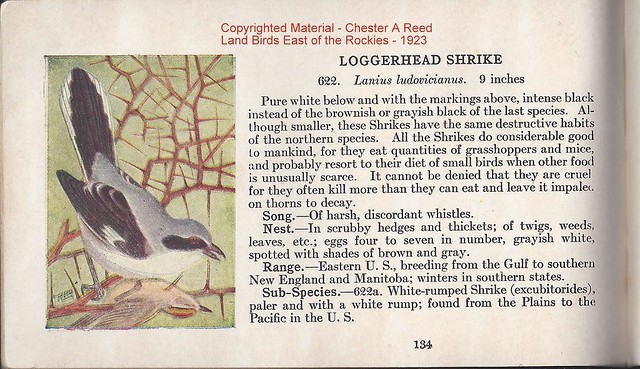

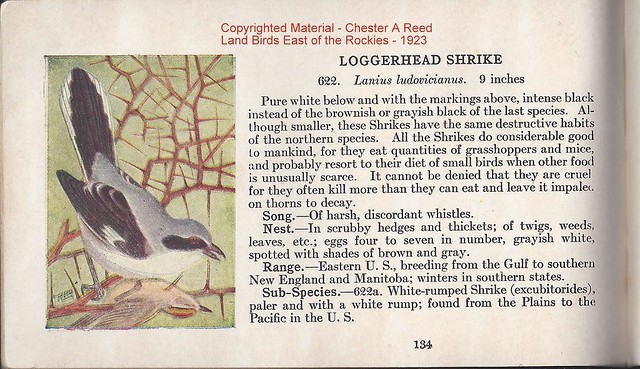

I did not know exactly what to call the bird, as nomenclature was confusing. My tattered little pocket Chester A Reed guide (published in 1923) called it a "Loggerhead Shrike." In those days birds were considered to be either "good" or "bad," but in Reed's opinion the shrike seems to straddle the line.

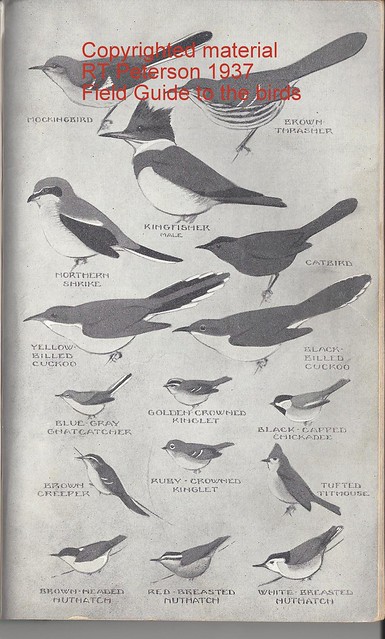

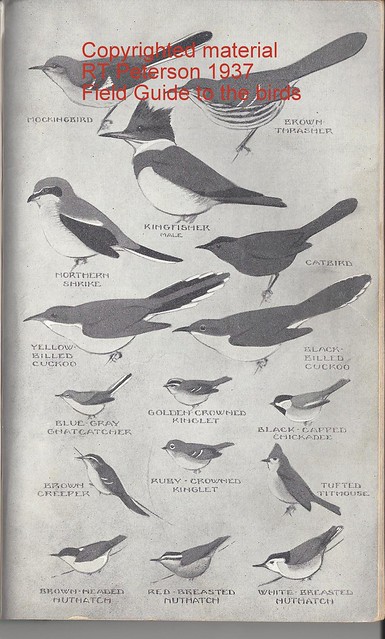

More up-to-date, my 1937 Peterson Field Guide to the Birds only illustrated the larger (and even less common) Northern Shrike:

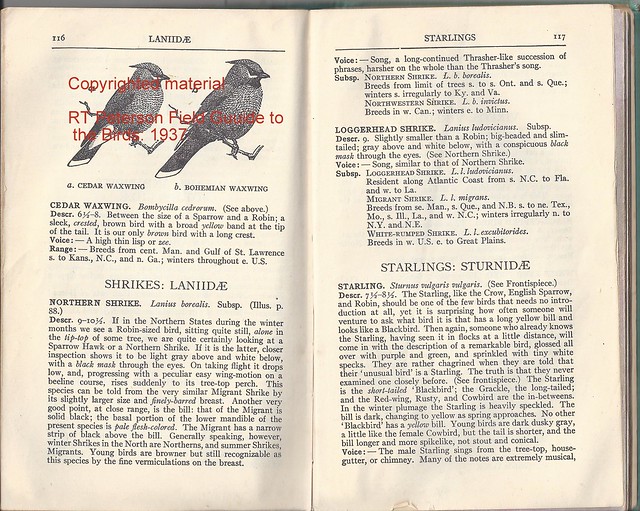

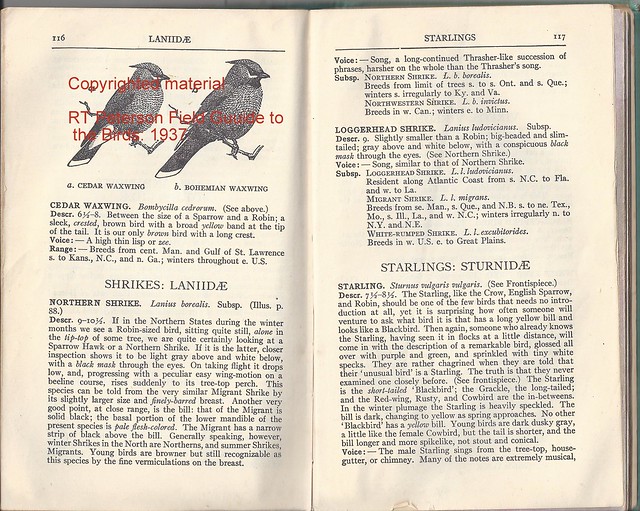

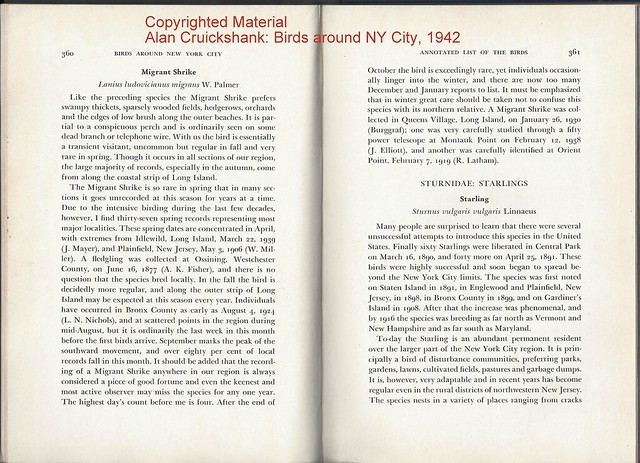

The text was not very illuminating, as it gave short shrift to the Loggerhead or Migrant Shrike as it was called:

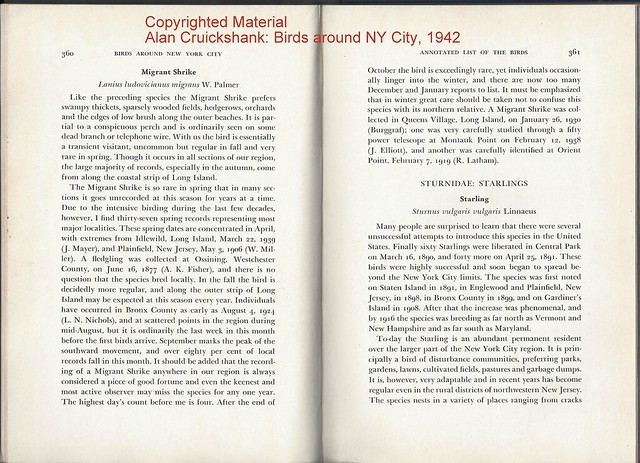

My "go to" reference for information about distribution and abundance was Allan Cruickshank's "Birds Around New York City (1942). I was elated that I had seen a relatively rare bird. Cruickshank reverted to calling it a "Migrant Shrike."

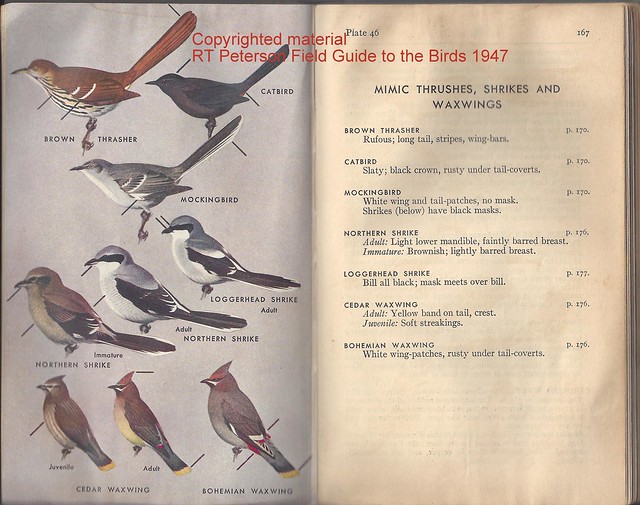

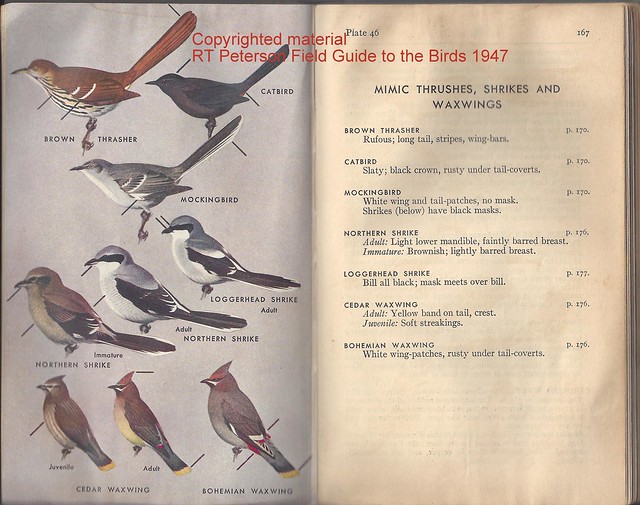

Only later, during the year of my first sighting, did Peterson's 1947 Guide appear, with the Loggerhead Shrike in all its glory.

During the 20 years following my sighting, the Loggerhead Shrike became more common in New Jersey, especially in the southern reaches of the state. However their numbers decreased and they once again became quite rare towards the end of the 20th Century up to the present. Ingestion of pesticides in insect prey is strongly suspected as the cause of their drastic decline. In south Florida, now my home, they are quite common breeders and winter visitors.

Cold light brings out the blue:

Their prey is varied, but mostly insects. I think this huge grub is a horsefly larva.

Except during the breeding seasons, Loggerhead Shrikes tend to be solitary. They often select the highest perch...

...and may be challenged by grackles...

...mockingbirds...

...and Blue Jays. In this case, the shrike retreated, possibly to simply avoid the company of others.

Yet, many time I have seen a shrike sit peacefully with a variety of other species, such as this American Kestrel...

...or a Northern Flicker.

One of my more remarkable shrike images includes two shrikes with a Belted Kingfisher and a kestrel, in late November.

In June the shrikes are courting.

I usually find it difficult to get any closer than 30-40 feet from a Loggerhead Shrike, but this fledgling was an exception.

The shrikes like to hunt for lizards on our back patio, so I can get some close views through the glass doors.

Parents watched this youngster as it unsuccessfully pursued a Brown Anole. They did not intervene, perhaps to teach their fledgling the importance of stealth and persistence.

Back in New Jersey on August 21, 1949 I saw my first Loggerhead Shrike. It was my Life Bird #119. Actually, a few days earlier I had found grasshoppers impaled on the spikes of a barbed wire fence in the Passaic River bottomlands a short walk from my home in Rutherford.

I had read about how the "Butcher Bird," whose "weak feet" lacked the talons of raptors, must stabilize its victims in this manner to permit them to be torn apart with its hooked beak. Hoping one day to see mice and small birds in a shrike's larder, I did not expect lowly insects. I searched for the shrike to no avail until three days later, when I caught sight of my "lifer."

I did not know exactly what to call the bird, as nomenclature was confusing. My tattered little pocket Chester A Reed guide (published in 1923) called it a "Loggerhead Shrike." In those days birds were considered to be either "good" or "bad," but in Reed's opinion the shrike seems to straddle the line.

More up-to-date, my 1937 Peterson Field Guide to the Birds only illustrated the larger (and even less common) Northern Shrike:

The text was not very illuminating, as it gave short shrift to the Loggerhead or Migrant Shrike as it was called:

My "go to" reference for information about distribution and abundance was Allan Cruickshank's "Birds Around New York City (1942). I was elated that I had seen a relatively rare bird. Cruickshank reverted to calling it a "Migrant Shrike."

Only later, during the year of my first sighting, did Peterson's 1947 Guide appear, with the Loggerhead Shrike in all its glory.

During the 20 years following my sighting, the Loggerhead Shrike became more common in New Jersey, especially in the southern reaches of the state. However their numbers decreased and they once again became quite rare towards the end of the 20th Century up to the present. Ingestion of pesticides in insect prey is strongly suspected as the cause of their drastic decline. In south Florida, now my home, they are quite common breeders and winter visitors.

Cold light brings out the blue:

Their prey is varied, but mostly insects. I think this huge grub is a horsefly larva.

Except during the breeding seasons, Loggerhead Shrikes tend to be solitary. They often select the highest perch...

...and may be challenged by grackles...

...mockingbirds...

...and Blue Jays. In this case, the shrike retreated, possibly to simply avoid the company of others.

Yet, many time I have seen a shrike sit peacefully with a variety of other species, such as this American Kestrel...

...or a Northern Flicker.

One of my more remarkable shrike images includes two shrikes with a Belted Kingfisher and a kestrel, in late November.

In June the shrikes are courting.

I usually find it difficult to get any closer than 30-40 feet from a Loggerhead Shrike, but this fledgling was an exception.

The shrikes like to hunt for lizards on our back patio, so I can get some close views through the glass doors.

Parents watched this youngster as it unsuccessfully pursued a Brown Anole. They did not intervene, perhaps to teach their fledgling the importance of stealth and persistence.

Friday, June 27, 2014

The Joy of Contributing to Florida's Breeding Bird Atlas

Posted by

Scott Simmons

Beginning in about the middle of May Central Florida begins to loose its migrants, and birds the breed in Florida begin to settle into to their breeding locations. And so June has become one of my favorite months of the year. Florida is currently conducting what's called a Breeding Bird Atlas. It's a wonderful opportunity for regular birders like me to contribute evidence concerning breeding birds so that scientists can have real data about what birds are breeding in Florida. This is the second atlas that has been conducted in Florida, so the data collected from this one can be compared to the data collected in the mid-80's. It's very gratifying to know that my hobby can be beneficial to science during the summer months.

Black-necked Stilts have been hanging at Marl Bed Flats just north of Lake Jesup. A couple weeks ago we began to see juveniles there.

My office parking lot has one adult and two baby Killdeer. It seems like they breed in my parking lot every year.

At sunrise and sundown we can sometimes see Common Nighthawks flying overhead. It's really fun to hear their courtship "boom" calls.

There's a colony of at least 75 or so Least Terns at a marina on Lake Monroe. This year I had the chance to see a couple together.

There's also a family of four American Kestrels at an electrical substation near my home. Most of our kestrels leave us for the summer, but our resident southeastern subspecies stays hear year round. The subspecies is actually a threatened species.

And Loggerhead Shrikes are also fun to find. There were at least 5 juveniles at the marina on Lake Monroe, still young enough to be fed by their parents.

|

| Juvenile Black-necked Stilt |

|

| Juvenile Killdeer |

|

| Common Nighthawk giving Courtship Call |

|

| Copulating Least Terns |

|

| JuvenileAmerican Kestrel (Southeastern Subspecies) |

|

| Juvenile Loggerhead Shrike |

Volunteering for the breeding bird atlas is fun, challenging and rewarding. If a survey like this is being done in your area, I highly recommend participating. It sharpens your observation skills and it makes summer birding all the more exciting.

Monday, June 16, 2014

Magnificent Warblers!

Posted by

Julie G.

Without a doubt, spring is my favorite season for birding. Exquisite migrating birds adorned in brilliant breeding plumage pass through the Midwest during the spring months. Birders, nature lovers and wildlife photographers delight in the dazzling beauty of feeding warblers throughout the migration season. This post features a variety of the magnificent warblers seen during this glorious period.

A stunning Chestnut-sided Warbler among the budding pink blossoms

A black-capped bird in pursuit of a meal ~ Wilson's Warbler

A brilliant Yellow Warbler pauses for a moment in the marsh

A secretive Kentucky Warbler searches for food amongst the leaf litter

A gorgeous Magnolia Warbler gleans insects from a budding tree

A handsome Black and white Warbler searches for bugs hidden in the crevices of tree bark

A secretive Kentucky Warbler searches for food amongst the leaf litter

A gorgeous Magnolia Warbler gleans insects from a budding tree

A handsome Black and white Warbler searches for bugs hidden in the crevices of tree bark

Crooning a tune ~ Hooded Warbler

A lovely Canada Warbler looks for nutrition amidst pretty pink blooms

Seeking a tasty treat of insects or larvae ~ Black-throated Blue Warbler

On the hunt for a buggy snack ~ Pine Warbler

Perched in the lush foliage ~ Blue-winged Warbler

A beautiful Prairie Warbler forages in low tree branches

A male American Redstart shows off his striking plumage

A lovely Canada Warbler looks for nutrition amidst pretty pink blooms

Seeking a tasty treat of insects or larvae ~ Black-throated Blue Warbler

On the hunt for a buggy snack ~ Pine Warbler

Perched in the lush foliage ~ Blue-winged Warbler

A beautiful Prairie Warbler forages in low tree branches

A Black-throated Green Warbler sports attractive feather markings

Spring is indeed a spectacular time for birding!

Posted by Julie Gidwitz ~ Nature's Splendor Blog - http://naturessplendor-julie.blogspot.com/

Friday, June 13, 2014

June Shorebirding, Sans-tundra

Posted by

Unknown

Michigan is blessed with some incredible shorebird stop-over habitat, thanks in no small part to our monstrous, sea-like lakes. April and May are always fun for the massive push of northbound birds, while July through October is the leisurely time to catch them all trickling back south. There's really only about a five or six week period centered on June that falls between the end of spring migration and the beginning of fall migration for shorebirds. That's when many of these birds are in the high arctic, laying eggs on the tree-less tundra. It's also when they look their best. The alternate (breeding) plumage for some of the shorebirds is simply exquisite. Sometimes late in the spring or early in the fall (which is actually mid-summer according to the shorebird calendar) we'll spot some that are nearly fully molted into alternate plumage or not yet molted out of it, but most of the time they're something like 70% "colored-up" in the spring, or badly worn and tattered in the summer.

This year, Sarah and I took an excursion to northern Michigan on the first weekend of June and were lucky enough to catch two of our favorite species lingering later than usual and showing off their best summer formal wear. Sarah got some great photos, some of which I'm sharing here.

Our first stop was at Tawas Point State Park on Lake Huron. Tawas Point is a notable migrant trap, renowned for its May warblers, but shorebirding there can be excellent. We got to see a couple of the critically endangered Great Lakes population of Piping Plover which have regularly nested on the beaches at Tawas Point for the past several years. There were plenty of Spotted Sandpipers, also summer nesters here, cavorting in the lagoons and bobbing their rear-ends at everything that passed.

Most of the migrants had moved on, of course, but an expected group of Semipalmated Sandpipers lingered, along with a few Sanderlings who were changing into their striking breeding plumage.

But the highlight at the point was a group of Ruddy Turnstones dressed to kill. (Not literally, unless you're an amphipod living under a beach pebble...then the turnstones most definitely are destined to kill you.) This has been Sarah's favorite shorebird since long before we had ever seen one and they were nothing more than fascinating pictures in the field guides. Our lifer came by random chance one fine mid-May day at Metzger Marsh in Ohio. Since then, we've seen dozens, if not hundreds, mostly in Florida where many of them winter. I remember a particularly hefty flock of them on a mudflat in Ding Darling National Wildlife Refuge one January. But all of those were in their basic (non-breeding) plumage. We just don't encounter them in alternate plumage much, mostly because we spend little time in the far north.

After taking our leave of the stragglers at Tawas Point, we headed to Lake Superior's southeast corner to see what was going on at Whitefish Point. There we braved a cold and blustery pebble-filled beach to spy another couple Piping Plovers, Sanderlings, and Semipalmated Sandpipers. But rather than turnstones, the treat here was one of MY favorite shorebirds, an American Golden Plover. This is quite a rare bird for June in Michigan, and this specimen was looking fine in his breeding colors.

A close examination through the scope revealed a bloody wound on the plover's shoulder, but it didn't appear to impede his flight as he crossed the point in the air right in front of us. Merlins like to hang out and nab small shorebirds at Whitefish Point, so it's possible this individual got in a tussel and fought a falcon to a draw. Regardless, it wasn't seen either before or after the day we were there, and I'd like to think he's above the Arctic Circle enjoying round-the-clock sun right now. I'm just glad he was slow enough with his migratory travels to let me have a look at him without having to drive to Nunavut.

|

| Spotted Sandpipers having a discussion at Tawas Point (Sarah Adams photo) |

|

| Piping Plover sporting the latest leg jewelry and piping at Tawas Point (Kirby Adams photo) |

|

| Sanderlings stopping over at Tawas Point (Kirby Adams photo) |

|

| Semipalmated Sandpiper (Sarah Adams photo) |

|

| Ruddy Turnstone, probably upset with the lack of stones to turn (Sarah Adams photo) |

|

| Ruddy Turnstones - leaving no stone un-turned and no crustacean un-consumed (Sarah Adams photo) |

|

| American Golden Plover, Whitefish Point (Sarah Adams photo) |

|

| American Golden Plover, Whitefish Point (Kirby Adams photo) |

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)